cordyline, wrought iron railings and white door

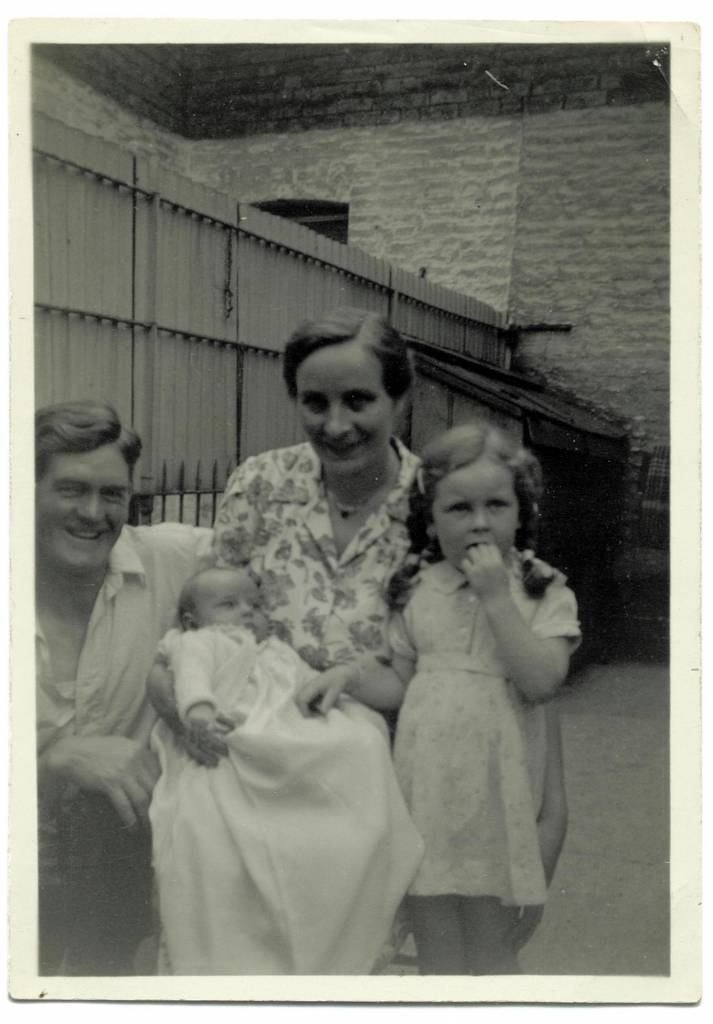

eldest daugther, Mary Emma and youngest daughter, Sarah Helen (known as Nellie) taken in a studio on Mill Road

Note the low shed behind that no longer exists – this might have been used for fuel of the fires.

What is now the Mill Road area of Cambridge was originally part of the historic estates of the Barnwell Priory. After enclosure, the area served as farmland and orchards, passing through the hands of several families and individuals, including the Barons Gwydyr.

The area began to be developed after the railway came to Cambridge in 1845. For a time, development was slow while the city considered creating a rail spur between the current station and the Parker’s Piece area, but once that plan was rejected by university dons who didn’t want the temptation of the railway too close to the university, development boomed. Beginning in the late 1860s, parcels of land were sold to developers who built dense terraced housing for railway workers and other working-class residents of the city. Between the 1860s and 1880s, 200 houses were built in Gwydir Street. Development began at the other end of the street before the rail spur was rejected, and the plots there were generally small and lacked front gardens. The houses at this end of the street were clearly meant to be slightly more upmarket, and although most still lacked features such as bay windows, the front gardens were attempts at gentility.

Gothic House, which is today the David Parr House visitor centre, was built at the key house of Gothic Terrace, of which the David Parr House forms a part, and it was one of the largest houses on the street. Along with the rest of the terrace, it was built in 1876, ten years before David purchased 186 to make his family home.

Although Gwydir Street was densely populated, it was not merely a residential area. By the 1901 census, the street also had butchers, greengrocers, fishmongers, a bakery, and a grocer. There were several public houses and a slaughterhouse on the street as well, meaning that in David’s time, the area would have been a bustling centre of commerce.

In the nineteenth century, Cambridge had an unusually high number of breweries for a city of its size, and brewing came to Gwydir Street soon after the area was developed. There was a Gwydir Brewery here by 1874, but the business passed through the hands of several owners, and by 1889 it had closed and been converted to stables.

In 1902, Frederick Dale revived the brewery, building a large premises that partially survives today. Wrought iron lettering proclaimed the name of the brewery not only on the three-story building that can be seen today, but on a five-story complex behind as well. The brewery bought many of the houses around it for its workers, and also had a warehouse and billiard room in Mill Road, just behind the Bath House. After winning medals in several brewery exhibitions between 1911 and 1919, Dale placed a seven-foot-high copper replica of a trophy cup above the tallest building to advertise his success. The brewery took over premises in Great Chesterford in 1913, and at one point Dales owned at least thirteen pubs in Cambridge and the surrounding villages.

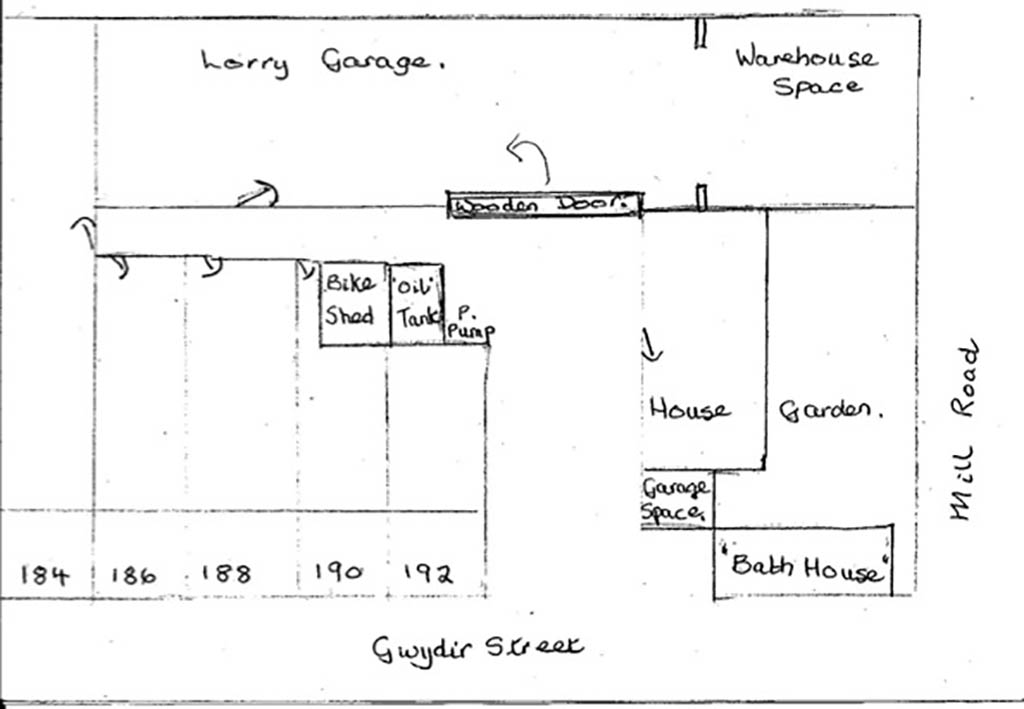

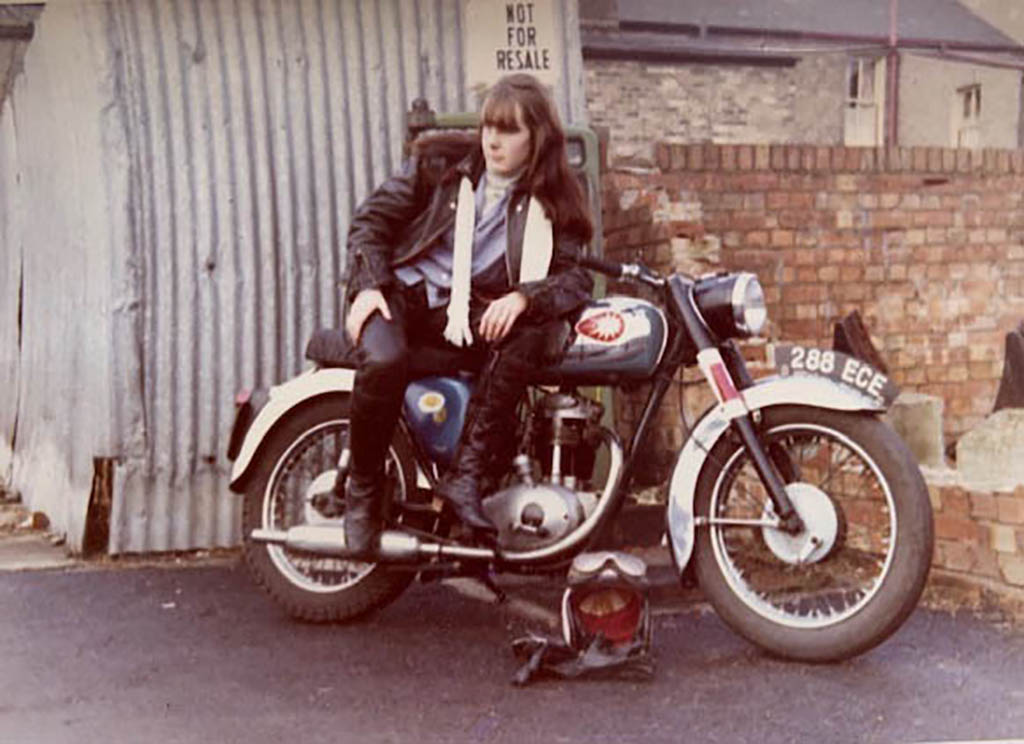

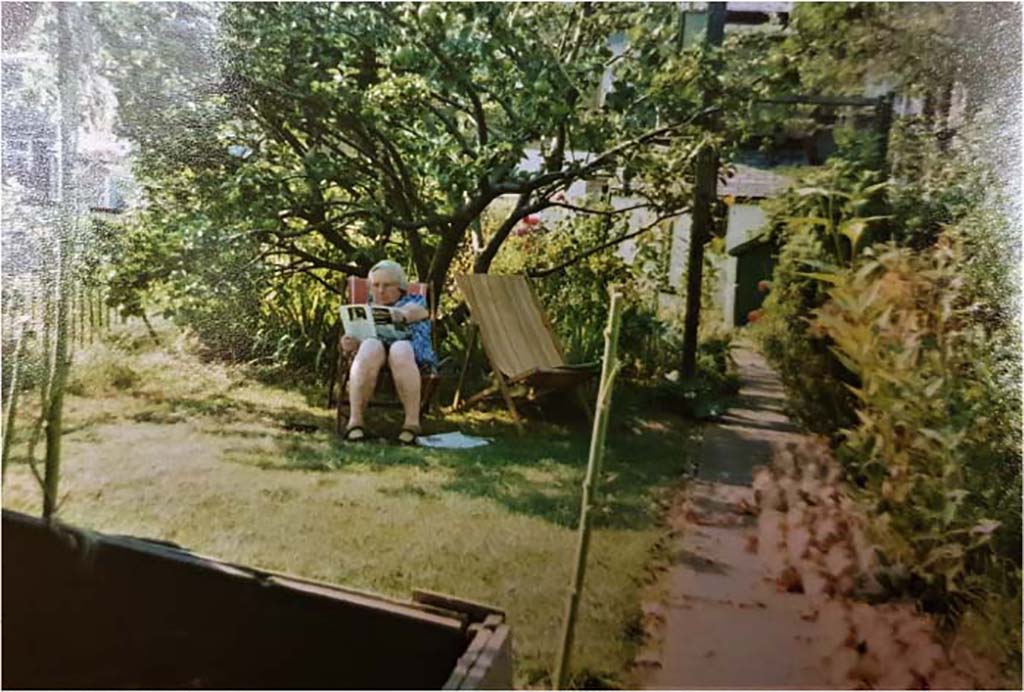

In David’s time, what is now the car park next to Gothic Terrace would have been a stables for the brewery’s horses, and in Elsie’s time, the stables was converted into a garage for lorries. Some of the garages were located immediately behind Elsie’s garden. At one point, the site was became a petrol station, and Rosemary, who was keen motorcyclist as a young woman still living at home, remembers using the pumps there.

As local brewing became rarer in the face of national mergers and acquisitions, Dales was sold to Whitbread, one of the largest brewers in the country, in 1955. The site became a bottling plant, then a store and a depot. The trophy cup was taken down in 1961. In 1966 Whitbread sold the premises to Cambridge City Council.

The Bath House is located on what was once the site of the grandest house on Gwydir Street, called Gwydir House. It was also known colloquially as the Doctor’s house.

It was compulsorily purchased in 1912 by the Borough of Cambridge, originally with a view to widening the road, but it seems then to have been used mainly as offices though at one time a school was proposed there. By 1919 the Borough was seriously considering the need for a Public Bath House. Some earlier plans to build one in 1877 to commemorate the Queens Jubilee on Laundress Green had come to nothing, perhaps because of opposition from George Darwin who lived behind the green in Newnham Grange (now Darwin College).

The need for such a place was undisputed. The population in Cambridge was rising rapidly and many families lived in overcrowded unsanitary conditions with limited access to fresh water. In these conditions, diseases such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, diphtheria, typhus and smallpox were frequent.

The Gwydir Street site became the preferred site of Cambridge’s public baths in 1923. The present building was built at a cost of some £7,800 and the Bath House was opened by the mayor in 1927, the year of David Parr’s death, and the year Elsie first came to live at the Parr House. By the 1970s, most houses in the area had installed bathrooms, and in the late 1970s, the building was converted into a community centre.

For more, see the Mill Road History Project Building Report from Capturing Cambridge: https://capturingcambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Bath_House_1st_edn_2015-10-14.pdf

.

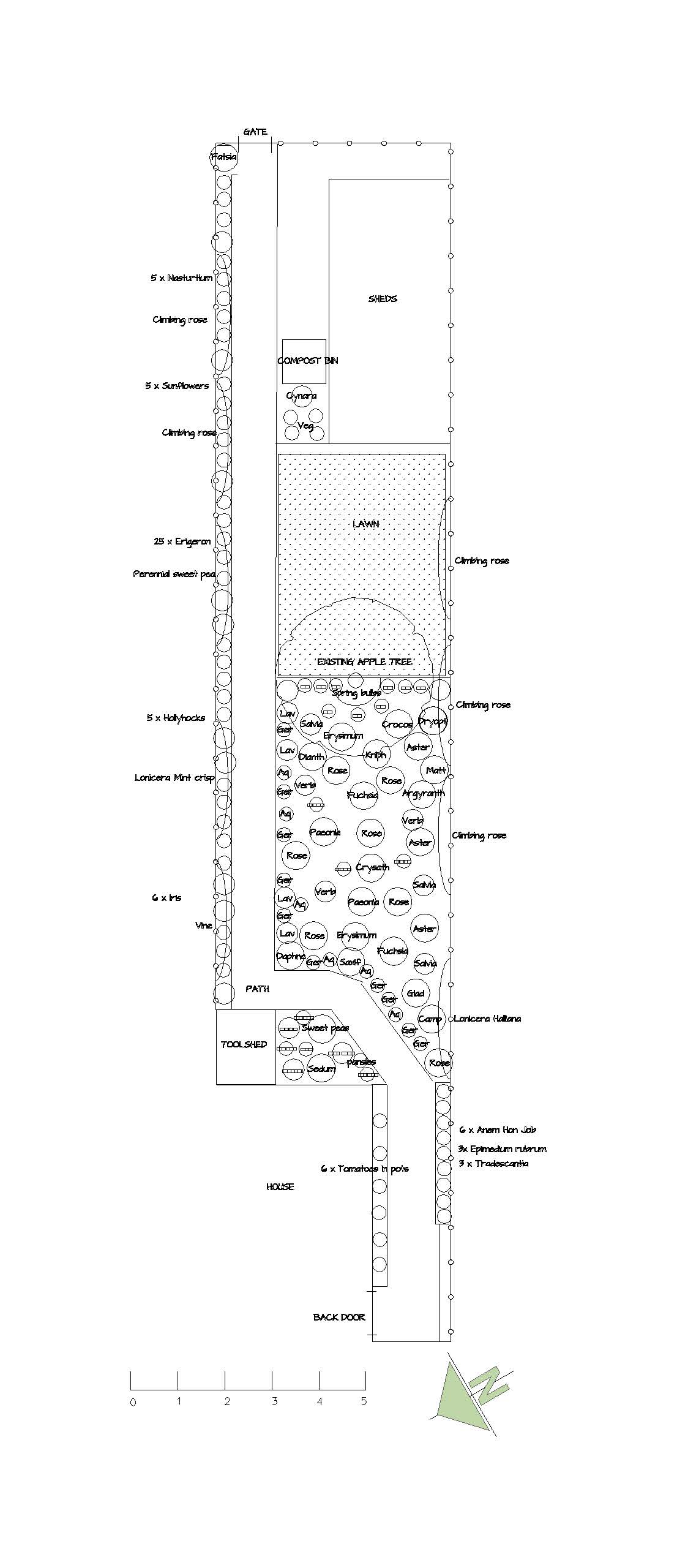

David Parr purchased wrought iron railings for his back garden in 1904, five years after he had installed iron railings in the front garden to replace an earlier wooden fence. At £9-9s-2d, the back railings would have been dear, but in keeping with David’s dedication to the Arts and Crafts ethos that so highly prized craftsmanship and quality, David’s railings were not mass-produced. Instead, they were made by Alsop & Sons, later the Britannia Works, of East Road, Cambridge. The firm was led by John Thomas Alsop, who called himself an ‘art iron worker and smith’.

Alsop & Sons served as wheelwrights, blacksmiths, fence makers, and cart makers in addition to being art iron workers. They even made horse-drawn preachers’ caravans, which Arthur Alsop, one of John Thomas’s sons, decorated with biblical texts. The firm made fences and railings that can still be seen across Cambridge today, including in Coldham’s Common, the Backs, Sheep’s Green, and the Cambridge City Cemetery. The firm hand-made the iron railings that still survive in the Parr House garden today.

David worked diligently to protect his artisan fence from the elements. Thanks to his notebook, we know that he painted it and removed rust every few years: in April 1905, then again in February 1908, and August 1914. He used lead-based paints to best protect the railings, and he seems to have used a variety of colours over the years, including ‘oil lead’ (a grey colour), ‘iron [lead]’ (a deep red), Manders white, and oil black. He may have also painted the finials a different colour to the rest of the railings.

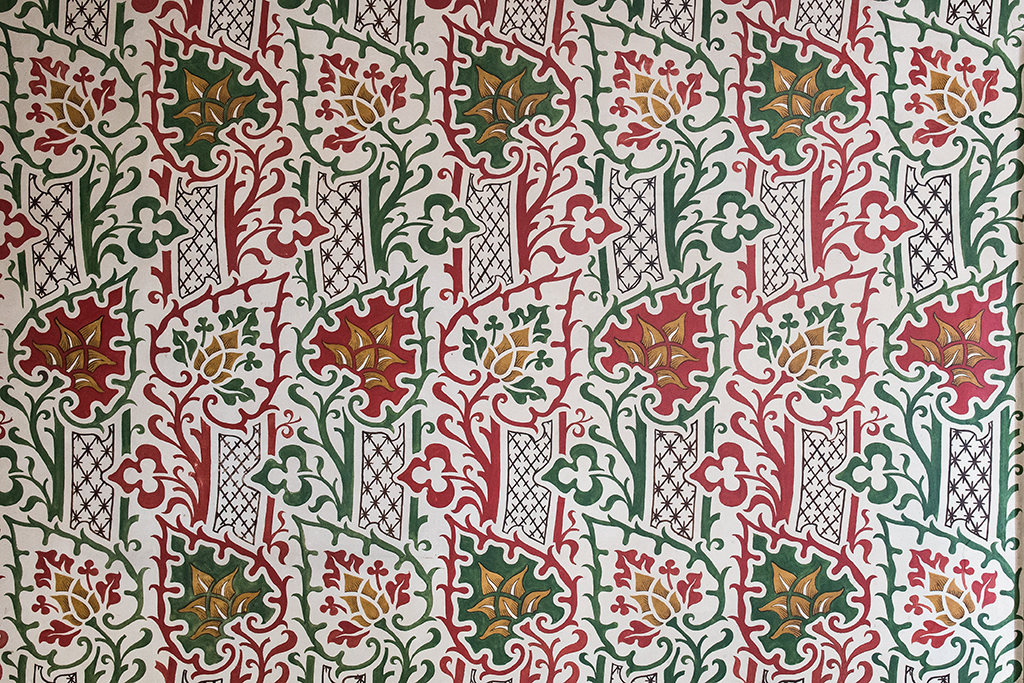

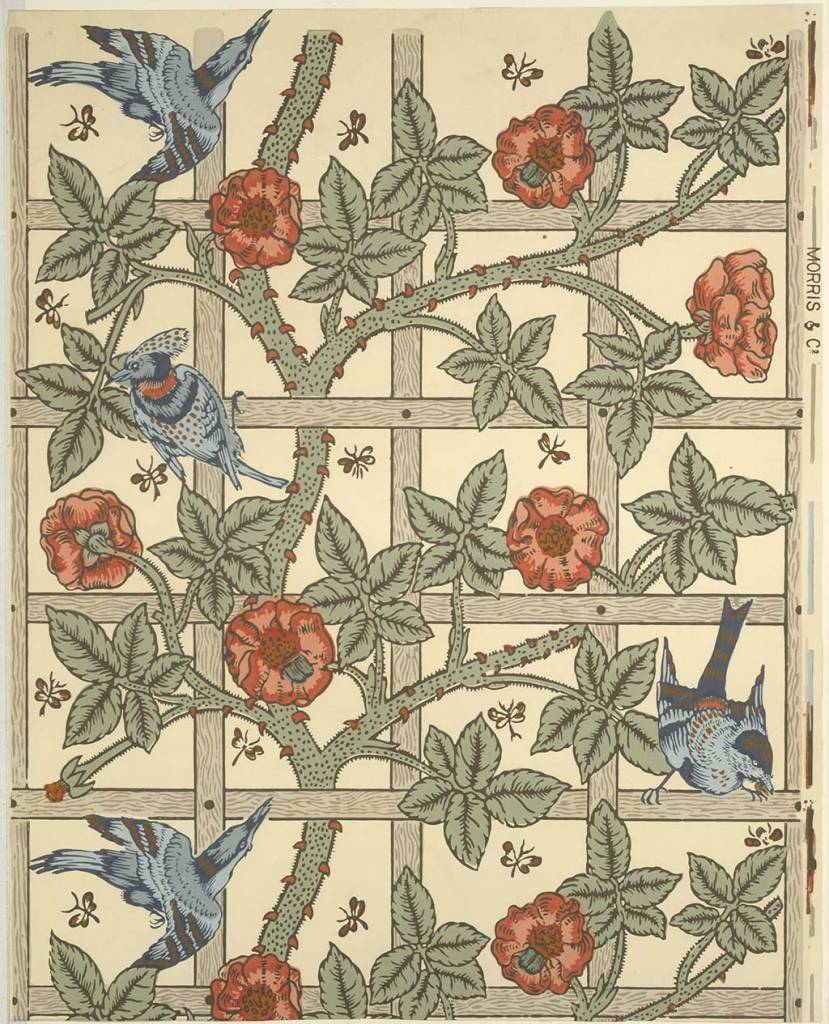

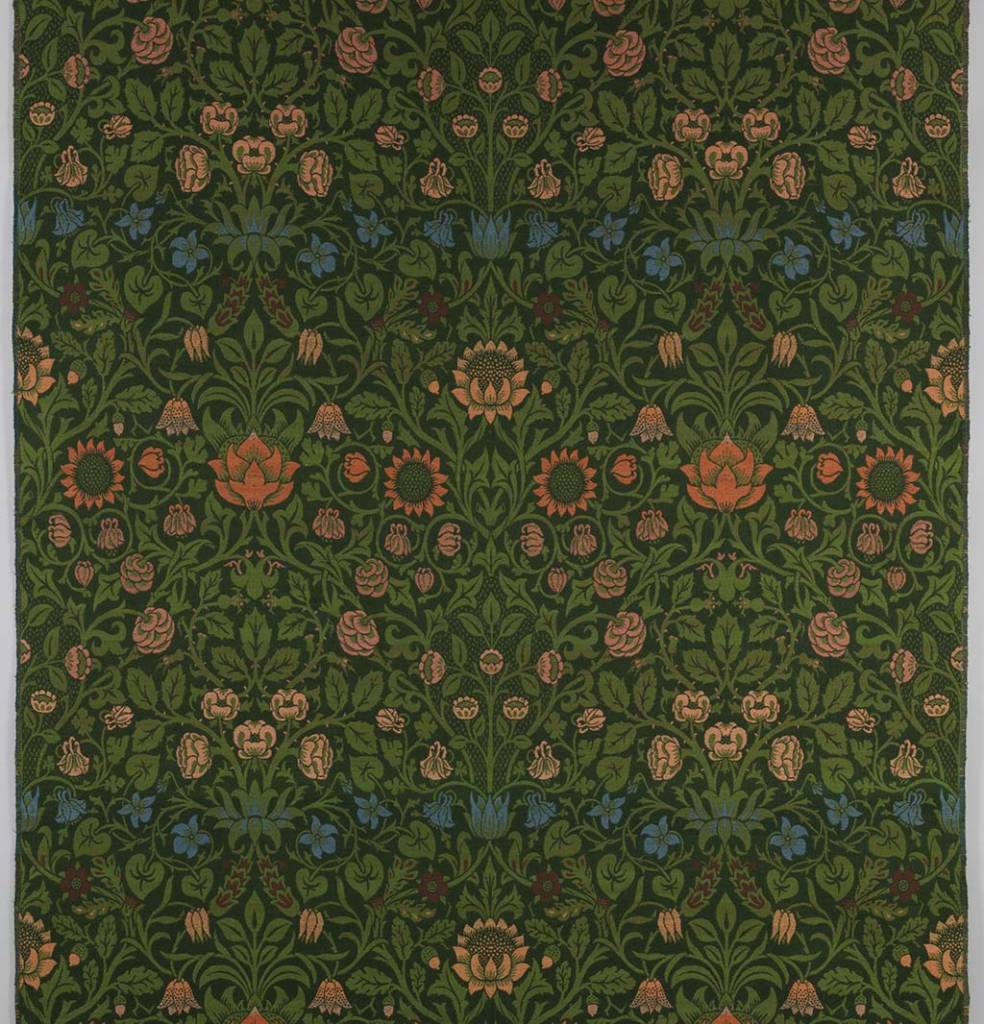

Today, the iron railings have been topped with a wooden trellis. Long common in gardens, trellises were also popular motifs amongst Arts and Crafts designers, including David himself: he used a lattice motif that rather resembles garden trellises in his 1918 bedroom decoration. Now that flowers are beginning to grow along the trellis, the contemporary arrangement more and more resembles William Morris’s trellis pattern of 1864.

Most of the artefacts by the kitchen door speak to David’s improvements to the house, and some are better understood than others.

There are the tantalising broken drainpipes made of salt-glazed stoneware of the type pioneered by Sir Henry Doulton to replace once-common wooden pipes. But there are also quarry tiles that were used in flooring both inside and outside the house, white glazed bricks from the Leeds Fireclay Company and the shallow bricks from the local Burwell Brickworks, and fragments of fire lumps that David likely installed for extra fireproofing at the backs of his fireplaces, and that Elsie and Alfred removed when they modernised the fires. The only suggestion of potential gardening comes from fragments of blue clay and salt glazed edging. David used similar materials to line the path from the door to the coal store in 1899, but such decorative tiles were often used to line flowerbeds as well.

Alfred Palmer built his shed in the waning months of 1947. It was a cold winter, when snow drifts reached the top of the front garden wall and the indoor toilet froze over, which probably necessitated spending more time than usual indoors. By then, Alfred and Elsie had been married for two years and were still living with Mary Jane in the Parr House, so it might not be too surprising that Alfred sought to carve out a space of his own during that cold winter.

From the end of October to the beginning December, he spent his time off work sourcing tin from Ridgeons, collecting reclaimed wood from the University Press, and buying tools. He worked when he could on the shed, building walls when he could, erecting posts when he had returned from rail journeys, but with David Douglas Parr’s help, it was still finished by early December. Alfred was clearly pleased with the work, for in his notebook he wrote, ‘Erected shed with Douglas’ help, very well done’.

In September 2018, over three consecutive days, and prior to the refurbishment of the back garden at the David Parr House, a community-based archaeological dig was undertaken. This was organised through a collaboration between David Parr House staff, Access Cambridge Archaeology and Cambridge Archaeological Unit. It was funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Sixteen small test pits, 80cm square, were dug around the garden and the contents carefully extracted and sorted by 47 local volunteers. The most prevalent finds were Victorian and twentieth century and can be associated with the lives of David and Mary Parr and the Palmer family who lived in the house after them. From David Parr’s time, over 600 sherds of domestic pottery, typical of what archaeologists would expect to find in this part of Cambridge at this time, were found. These included some transfer printed ware and imported Chinese porcelain. The second most common finds were pieces of what the experts refer to as “Horticultural Earthenwares” – no prizes for guessing they are talking about flower pots! Some of these were identifiable as having been manufactured by Sankey’s of Bulwell, Nottinghamshire. Interestingly, there was very little glass found in the soil. David Parr perhaps reused glass jars in his work, or glass was generally carefully recycled, as the Victorians wasted little.

There were some more personal items too. In the area where the washing line had hung were found various buttons, a pair of tweezers and some coins. One coin dated from 1895; there was also a 1938 threepence and a sixpence from 1951. Clay tobacco pipe fragments can be relatively easily dated by experts, so it was possible to tell that many of the pipe pieces found were from the nineteenth century. Even the Palmer family pets left their traces in the earth. There were the remains of at least three individual guinea pigs, although Elsie Palmer’s daughters only speak of two guinea pig pets – Valentina and Squeaky. No bones of Elsie’s canary, Dick, were identified. Rabbit bones were discovered (there had been a pet rabbit called Whisky) and the hens that used to live in Alfred’s hen house may be represented in some excavated chicken bones. A partial rodent skull was also unearthed along with that of a mallard. Other items from past family life included glass marbles, the arm of a small doll, the green foot of a Mr Potato Head and a bubble blowing stick, as well as an Enid Blyton Club Magazine badge which can be dated to between 1953 and 1959 as the Club was relatively short-lived.

The dig also revealed signs of the area’s more distant past. Prior to the second half of the nineteenth century, the Mill Road area had been fields and market gardens with the route of Mill Road marked by a trackway leading to Cherry Hinton called Hinton Way. Pieces of pottery dating from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries were discovered in David Parr’s garden. The most common type found is known as “Redware”, which is reddish brown earthenware pottery, but there were also sherds of “Creamware” (cream-coloured glazed earthenware) and salt-glazed Staffordshire stoneware and slipware, with its characteristic marbled or combed patterns, along with pottery from Derby and a few sherds of imported German pottery. As there were no dwellings in this area between the Middle Ages and the nineteenth century, it is suggesed that this pottery is associated with what the archaeologists refer to as “agricultural manuring of the fields.” Pieces of clay pipe from a similar time period are also likely to have come from agricultural workers.

Looking even further back in time, five of the pits contained sherds of pottery from the time period 1066-1400; six pieces in all, the majority of which were found along the southern edge of the garden. There were relatively low levels of late Anglo-Saxon pottery. Although the centre of Anglo-Saxon Cambridge was in the area around Magdalene Bridge, some distance away, some Anglo-Saxon artefacts have in the past been discovered in the Mill Road area, such as a shield boss and spearhead in Mill Road cemetery; although no human remains have been found from this period in this area.

There was nothing revealed from the days when the Romans were here, their settlement having been in the Castle Hill area of Cambridge. A small number of Romano-British finds have been identified within a 500m radius of Gwydir Street, including a single Roman coin, but nothing in David Parr’s garden itself.

There were some signs of life in prehistory, however. Although no really ancient pottery was discovered, there were some flints that the archaeologists thought may have been worked by ancient people and 35 pieces of burnt stone were found, suggesting that ancient fires were being lit in the area.

As well as enhancing the picture we are piecing together of the residents of 186 Gwydir Street and the history of the surrounding area, the David Parr House dig provided an opportunity for members of the local community and volunteers at the house to take part in an archaeological dig for the first time, which proved a fascinating and enjoyable experience and a chance to contribute to background research for the Trust.

If you would like to discover more detail about the dig and the archaeology of this part of Cambridge, the full report, by Catherine Collins, is available on the Access Cambridge Archaeology website.

Based on the ACA “Archaeological Excavations at David Parr House, 184/186 Gwydir Street, Cambridge in 2018” by Catherine Collins, 2019.

For centuries throughout the world, flowers have been imbued with symbolic meaning, but in the Victorian era, floriography, or the language of flowers, became enormously popular. In an era that saw a new emphasis on propriety, especially between suitors, and in a culture that frowned upon excessive displays of emotion, flowers became a way people could subtly exchange messages. The meanings of flowers were based on a wide variety of factors, including folklore, religious symbolism, and the characteristics of plants themselves, and floral dictionaries became a popular new form of literature, interpreting the meanings of plants and colours for senders and recipients. Gardening was an enormously popular hobby in the Victorian era, and people still commonly wore or carried small bouquets known as posies or tussie-mussies. These small arrangements were most commonly exchanged, although larger bouquets could be presented as well.

Flowers and botanicals were extremely popular motifs with Arts and Crafts artists. Painters imbued their art with symbolism through the flowers they placed around their subjects, and in the decorative arts, stylised botanicals were in abundant use. William Morris’s designs for paper & textiles drew heavily on the natural world, while not being concerned with botanical accuracy. David’s ability to adapt, refine and manipulate Morris & Co designs is shown in the ‘ornament’, or pattern, he designed for his walls. Flowers David painted include tulips, lilies, dianthus, Michaelmas daisies, and foliage such as acanthus leaves. Like his contemporaries, David’s designs were stylised as well.

For more on the Victorian language of flowers, see the English Heritage blog: https://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/what-can-history-teach-us-about-the-language-of-flowers/

The garden is now carefully tended by our garden volunteer Elizabeth McKellar, who keeps a garden notebook in the tradition of Alfred, and who shares her musings on our website

Listen as neighbour Janet remembers Elsie’s generosity with the fruits of her garden.

When Janet first moved in, Elsie left a bouquet of cornflowers and a note that said ‘welcome’ on Janet’s garden gate. Elsie gave Janet apples and also offered her anything else from the garden, so Janet transplanted some of Elsie’s bluebells to her own garden. As an immigrant, Janet saw Elsie’s garden as an ideal English cottage garden: ‘she loved it and every year you saw the result of her devotion to it’.

Listen as neighbour Joan remembers Elsie and the garden

Joan and Elsie cut the hedge between their gardens level ‘like a table’, and they used to exchange food using that hedge. Elsie left apples, and Joan would put out tins of her baking and portions of soup in a small saucepan, which Elsie would savour for supper over a few days.

‘As a close neighbour of the David Parr House on Gwydir Street and a member of the volunteer team I was delighted to be asked to exhibit three pieces of work in the garden of the visitor centre.

Working as a stonemason over the last 35 years I’ve worked on a number of historic buildings and church buildings, and I’m proud to be part of a continuing local artisan tradition and to share a fascination with the joys of surface pattern.

All cut and carved stonework is a controlled manipulation of the play of light and shade upon the surface, whether hard lines and edges or soft and rounded curves. This work grows out of an interest in archaeology, artefacts, archetypes, imagined times and places using the skills and disciplines of architectural stone masonry and carving.

Pattern and rhythm appear in the earliest artforms and still fascinate the human mind; finished and polished surfaces with broken and fractured edges evoke wonder about possible pasts and futures.

Neither abstract nor representational in the conventional sense, the work is essentially about time, both individual and subjective time and our collective and cultural time.’

Mark Radcliffe Evans, November 2019

Work is for sale and a price list is available. 25% of the sale price will be donated to the David Parr House.

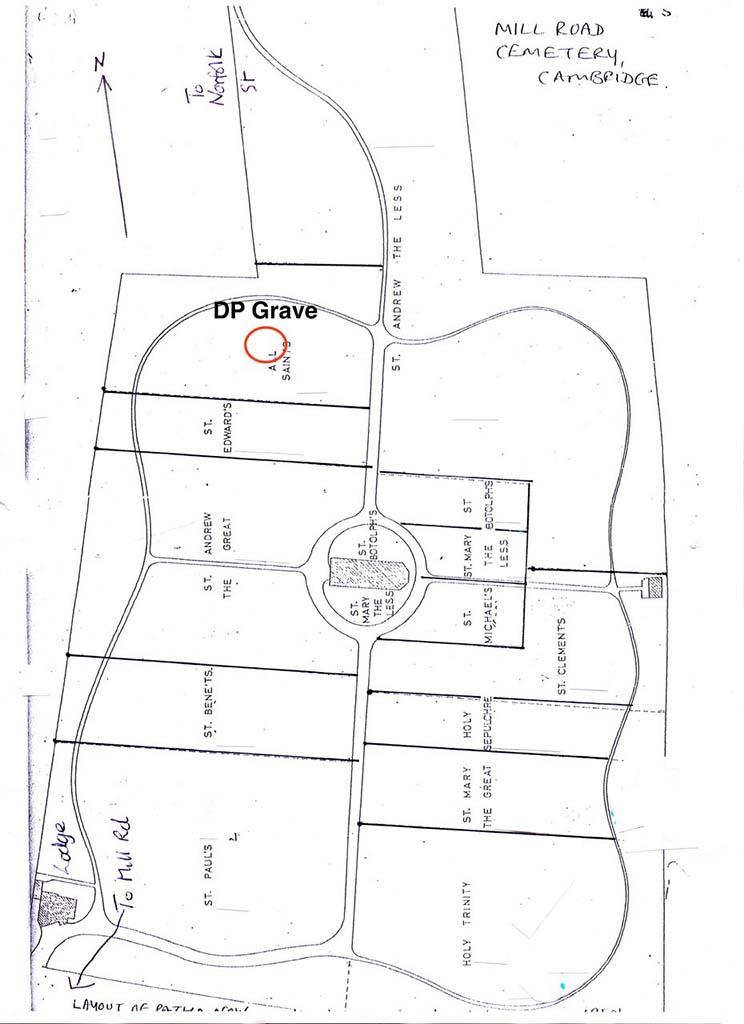

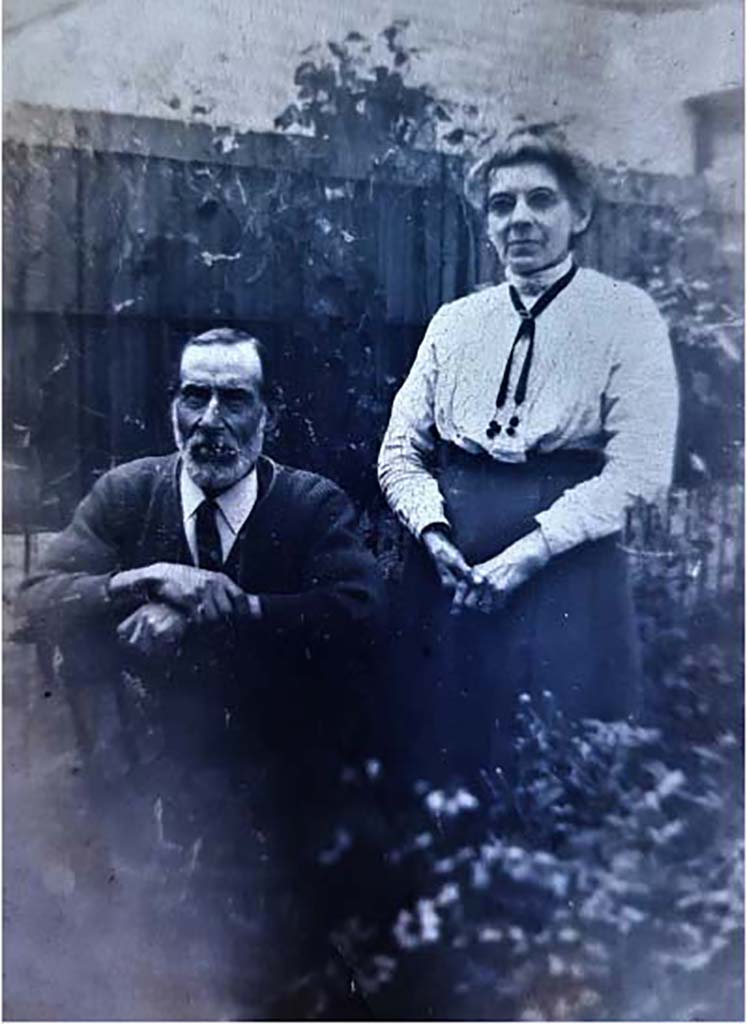

David Parr and his wife Mary Jane are buried in the All Saints section of the Mill Road cemetery. Their grave is marked by a simple set of kerbstones.

You can visit the grave by returning to Mill Road, turning right up the road until you reach the Avenue of Limes just before Mackenzie Road, and then following the paths up to the northern section of the cemetery. Please use this link to open up Google Maps. Please see the map for the specific location of the grave.

By the end of the 1830s, there was a shortage of burial space in Cambridge: churchyards were full or overcrowded, and there was little room to expand as the city had grown around the churches.

People were concerned about shallow graves in overcrowded churchyards and a potential link to the spread of disease. After several years of deliberation and fundraising and the opening of a public cemetery north of the city, in 1847 a parcel of land just off Mill Road was purchased for the use of thirteen Anglican parishes. The new cemetery was designed by Andrew Murray, who also designed the Cambridge University Botanic Garden. The first burials took place in 1848.

A lodge was built to accommodate a custodian who oversaw the cemetery, but each parish was responsible for the upkeep of their designated area. In 1858, a chapel designed by George Gilbert Scott was erected in the centre of the cemetery to better accommodate funeral readings that had been taking place in the lodge. As the cemetery filled and was used less frequently for new burials, the chapel fell into disrepair, and after a fire, it was taken down in 1954. Today the former site of the chapel is outlined in carved York stone.

For more information about the cemetery, see http://millroadcemetery.org.uk/